Provenance

Possibly, Louisine Elder (Mrs H.O. Havemeyer), 1880

Sra Josefina Unzué de Cobo, Buenos Aires, 1900

Sra Sara Maredo Unzué de Demaria, Buenos Aires, 1958Private collection, Buenos Aires

Exhibited

Paris, Salon, 1880, no. 1820

Literature

Paul Mantz, “Le Salon de 1880,” Le Temps, 23 May 1880, n.p.

Daniel Bernard, “Salon de 1880,” L’Entr’acte, 6 June 1880, n.p.

“M. Henner”, Le Libéral de l’est, 20 May 1880, np.

François-Guillaume, Le Salon : journal de l'exposition annuelle des beaux-arts, Paris, 1880, p.130.

Louis Enault, Guide du Salon, Paris, 1880, p. 9.

Paul de Charry, “Le Salon de 1880,” Le Pays, 23 May 1880, np.

Daniel Bernard, “Salon de 1880,” L’univers illustré, 5 June 1880, p. 318.

Eugène Montrosier, Les Artistes modernes, vol. II, Les Peintres du nu, Paris, Librairie Artistique, H. Launette, n.d., p. 103.

Albert Thiébault-Sisson, “Jean-Jacques Henner et son œuvre,” Les Lettres et les Arts, Paris, January 1899, p. 85.

Émile Cardon, “Artistes contemporains, esquisses et portraits – V – J.-J. Henner,” Le Moniteur des Arts, 25 October 1895, p. 336.

Catalogue général des reproductions inaltérables au charbon d’après les originaux, peintures, fresques et dessins des musées d’Europe et collections particulières les plus remarquables et des œuvres contemporaines, Dormach, Paris and New York, 1896, no. 855, p. 313.

Albert Soubies, J.-J. Henner (1829–1905): Notes biographiques, Paris, Flammarion, 1905, p. 6.

Léon Lhermitte, Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. Henner, peintre de l’Académie, lue dans la séance du 26 mai 1906 de l’Académie des beaux-arts, Paris, Firmin-Didot, Institut de France, Académie des beaux-arts, 1906, p. 27, 41.

Tristan d’Estève, “Les morts de 1905: Jean-Jacques Henner,” Les Arts, no. 49, 1906, p. 22.

Émile Blémont, “J.-J. Henner,” Artistes et penseurs, Paris, Alphonse Lemerre, 1907, p. 74, 76.

Léonce Bénédite, “Jean-Jacques Henner, septième article,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, ser. II, no. 40, 1908, p. 145.

Samuel Rocheblave, “Jean-Jacques Henner,” Revue alsacienne illustrée: Biographies alsaciennes, no. XXVIII, 1911, p. 21, 30.

Louis Loviot, J.-J. Henner et son œuvre, Paris, Engelmann, 1912, p. 19, 45, 46, 51.

Henri Roujon, Les Peintres illustres: Henner, Bibliothèque artistique et couleurs, no. 40, Pierre Lafitte et Cie éditeurs, 1912, p. 62.

Émile Durand-Gréville, Entretiens de J.-J. Henner: Notes prises par Émile Durand-Gréville après ses conversations avec J.-J. Henner (1878–1888), Paris, Alphonse Lemerre, 1925, p. 146, 147.

Pierre-Alexis Meunier, La Vie et l’art de Jean-Jacques Henner: Peintures et dessins, Washington, Flammarion, 1927, p. 36, 38.

Isabelle de Lannoy, Jean-Jacques Henner (1829–1905): Essai de catalogue, typed thesis, École du Louvre, directed by Geneviève Lacambre, unpublished, 1986, no. 457, p. 993–998.

Isabelle de Lannoy, Henner, Catalogue raisonné, Paris, Musée National Jean-Jacques Henner, 2008, vol. I, no. C490, p. 369, ill.

Catalogue note

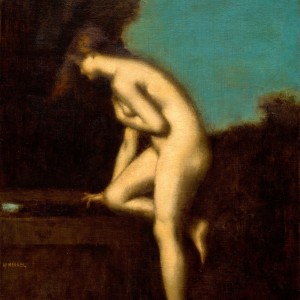

Jean-Jacques Henner’s La Fontaine belongs to the most atmospheric phase of the artist’s mature production, when his mastery of the female nude—rendered in softly dissolving contours against a velvety darkness—had become one of the defining signatures of late nineteenth-century French painting. Exhibited at the Salon of 1880 (no. 1820), the present canvas is one of the rare, fully realized versions of the motif that preoccupied Henner in the preceding year: a solitary nymph bending beside a woodland spring at the threshold of dusk. The subject allowed Henner to distil all the qualities for which he was praised by contemporary critics: an almost musical chiaroscuro, an idealized female form held in suspension between visibility and evanescence, and a dreamlike, crepuscular atmosphere that recalls both Corot and the tonal poetics of the Symbolist generation.

The emotional register of the composition is deepened by the poetic quatrain of Georges Lafenestre (1837-1919), affixed to the original frame of the present painting. Lafenestre, one of the period’s leading Salon critics, wrote:

Heure silencieuse où la nymphe se penche

Sur la source des bois qui lui sert de miroir

Et rêve en regardant mourir sa forme blanche

Dans l’eau pâle où descend le mystère du soir.

Silent hour when the nymph leans down

Over the woodland spring that serves her as a mirror,

And dreams as she watches her white form fade

In the pale water where the mystery of evening descends.

More than an ornamental caption, the verse articulates the very quality Henner sought to achieve: a scene in which the nude hovers between reflection and disappearance, absorbed into the “mystère du soir.”

Archival materials in the painter’s diaries and correspondence reveal that Henner produced two versions of La Fontaine in close succession. The first, commissioned by Madame Charras in 1879, is now in the Musée Henner in Paris. The second—of which the present painting appears to be a candidate—is the version sent to the Salon in March 1880 and subsequently sold on 1 May of that year for the then-remarkable sum of 15,000 francs to a buyer recorded in the artist’s notes under the approximate spelling “Ehrler,” long recognized as referring to the American collector Louisine Elder (later Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer), who was introduced to Henner by Mary Cassatt (1844-1926). While the Havemeyer ownership cannot yet be firmly confirmed, it is consistent with their early engagement with Henner’s work and with the documented presence of La Fontaine in their circle.[1]

By the early twentieth century, the painting had entered an important Argentine collection associated with the distinguished Unzué family, prominent figures in the cultural and philanthropic life of Buenos Aires. Closely connected to the city’s Francophile elite, members of the family were active patrons of architecture, the decorative arts, and public institutions, and are documented among the donors to the Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo following its inauguration in 1938. Assembled at a moment when South American elites sought to align local taste with the artistic models of Paris, collections within the Unzué family circle—shaped by sustained engagement with French culture and travel—played a significant role in preserving and disseminating works of French academic and post-academic painting beyond Europe.[2]

La Fontaine thus stands at a rich intersection of Henner’s artistic refinement, poetic reception, and international collecting history. Its serene, dusk-laden reverie is matched by a provenance that traces the transatlantic journeys of French art at a moment of expanding global modernity.

This note was written by Elsa Dikkes.