Provenance

E. Jung, Winterthur, by 1898

Hans Reinhart, Winterthur, 1939

Lilly Edelmann-Nager, Küsnacht, Switzerland, 1963

Thence by descent (and sold: Sotheby’s, London, 23 November 2010, lot 4)

Private collection, California (acquired at the above sale)Exhibited

Basel, Kunsthalle, Basler Kunstverein, Böcklin-Jubiläums-Ausstellung, 1897, no.13

Winterthur, Kunstmuseum, Der Winterthurer Privatbesitz, September-October 1942, no. 35, 17

Basel, Kunstmuseum, Basler Kunstverein, Arnold Böcklin: Gemälde, Plastiken. Ausstellung zum 150 Geburtstag, 11 June-11 September 1977, no. 25

Zürich, Kunsthaus, 3 October 1997-18 January 1998; Munich, Haus der Kunst, 3 February-3 May 1988; Berlin, Nationalgalerie, 29 May-10 August 1998, Arnold Böcklin, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst: Eine Reise ins Ungewisse, no. 7, 436, ill. 134

Basel, Kunstmuseum, 19 May-26 August 2001; Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 23 October 2001-13 January 2002; Munich, Neue Pinakothek, 14 February-26 May 2002, Arnold Böcklin, no. 5, 148

El Segundo, Museum of Art, 13 October 2014-1 February 2015

Literature

Henriette Mendelsohn, Böcklin, Berlin: E. Hofmann & Co., 1901, pp.32-34, 78, 107

Heinrich Alfred Schmid, Verzeichnis der Werke Arnold Böcklins, Munich, Photographische Union 1903, no. 40

Karl Woermann, “Zur Baseler Böcklin-Ausstellung 1897,” Von Apelles zu Böcklin und weiter: Gesammelte kunstgeschichtliche Aufsätze, Vorträge und Besprechungen, Esslingen am Neckar, P. Neff, 1912, vol. 2, p.157

Richard Hamann, Die Deutsche Malerei im 19. Jahrhundert, Leipzig-Berlin, Teubner, 1914, pp. 188-189 (as Reiter im Mondschein)

Günther Kleineberg, “Die Entwicklung der Naturpersonifizierung im Werk Arnold Böcklins (1927-1901): Studien zur Ikonographie und Motivik in der Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts,” Dissertation, Göttingen, 1971, pp. 41, 42, 44, 185

Rolf Andree, Arnold Böcklin: Die Gemälde. Basel-Munich, F. Reinhardt-Prestel, 1977, no. 55, p. 202

Catalogue note

When Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) completed his symbolist masterpiece, The Isle of the Dead, in 1880, he was arguably the most famous contemporary artist in the German-speaking world (Cat 2a).[i] Few have failed to point out the Romantic roots of his evocative yet inexplicable canvas or of the haunting imaginary landscapes that preceded it (Cat. 2b). Decidedly more have failed to acknowledge the Düsseldorf origins of Böcklin’s art of mystery and sustained ambiguity. Yet his enigmatic figures who, passing our way without further explanation, stir up subliminal unease would not have been born without the tutelage of Carl Friedrich Lessing (1808-1880).

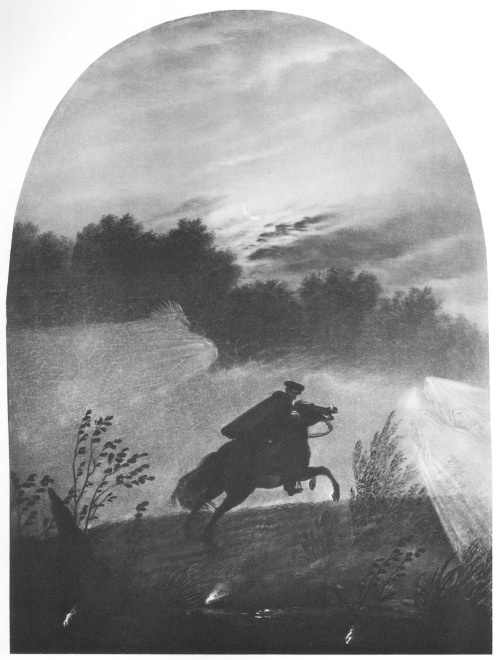

Although Böcklin’s earlier compositions betray a deeply rooted fascination with seventeenth-century Dutch masters like Ruysdael and Hobbema, Böcklin had little formal training. The little he had he did receive from 1845 to 1847 at the Düsseldorf Academy, where he studied under Johann Wilhelm Schirmer (1807-1863). The experience proved transformative. Enthralled, the younger painter adopted many of his teacher’s signature traits: a meticulous rendering of plants, love for dramatic cloud formations and obsession with expressive groups of trees often placed right at the center of a composition. But nothing had a longer lasting influence on Böcklin that the kind of cryptic story-telling that Lessing had so successfully explored in his 1830 hit canvas, The Mourning Royal Couple (see Fig. 15). By the time Böcklin arrived at the Rhine, the mysterious anthropomorphism of Lessing’s soul-painting had made his way into landscape as well. The Swiss painter picked up where his mentor had left of, and in 1849, he painted the first work that explicitly prompted the viewer to associate freely what picture’s narrative might be (Cat. 2c). As such, his Moonlit Landscape with Ruin is not only a key work in Böcklin’s oeuvre, but a key to his work.

Böcklin painted this charged early landscape when merely twenty-two. With its distinctly Romantic overtones, the painting synthesized his most formative artistic influences, from his Düsseldorf mentors, Schirmer and Lessing, to the German Romantic painters more generally and in particular Carl Blechen (1798-1840), Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) and Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869). Indeed, Carus’s 1825 rendition of the Erlking is often cited as an immediate model (Cat. 2d). The agitated and stirring atmosphere of Böcklin’s landscape certainly captures the traumatic experience of the cursed eponym of the 1782 poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832):

Who rides there so late through the night dark and drear?

The father it is, with his infant so dear;

He holdeth the boy tightly clasp'd in his arm,

He holdeth him safely, he keepeth him warm. …

The father now gallops, with terror half wild,

He grasps in his arms the poor shuddering child;

He reaches his courtyard with toil and with dread,

The child in his arms finds he motionless, dead.[ii]

We feel a primordial terror reading these lines, and we feel the same watching the dark silhouette of Böcklin’s rider making his way across the storm-ridden landscape. Not surprisingly, he would return three decades later with a much more macabre destination mapped out, Death’s Ride (Schack-Galerie, Munich). Yet for all our unsettling premonitions of impending doom, in 1849, we will look in vain for the Erlking’s child. The literary reference maybe suggestive but it is pure speculation. Like Carl Friedrich Lessing before him, Arnold Böcklin, too, leaves us guessing.

And guessing we will! What is the story, we inevitably ask ourselves, behind the landscape’s gripping drama? Why is the incoming tempest chasing those billowing clouds across a stormy sky? And what about the overgrown ruin below cast in such garish light? As we hurry through the landscape in search of meaning, the crumbled church turns into a somber metaphor for the passing of time and the inescapable demise of all things terrestrial, not least of ourselves. The rider and drifting clouds add to this mood of transience. Yet for all its timeless universality of the picture’s intense struggle with the fall of all human endeavors, Böcklin’s Romantic memento mori might also have held a more personal meaning for the artist. Only a year before the canvas’s completion, Böcklin had witnessed the bloody events of the 1848-Revolution in Paris firsthand. The violence of the insurrection and its brutal suppression left a deep impression on the Swiss artist, who reputedly watched as soldiers herded a group of ragged prisoners past his apartment near the Jardin du Luxembourg. Böcklin would distill this autobiographical moment into images of our collective human experience.

Painted in 1849, The Moonlit Landscape with Ruin holds a special place in Böcklin’s oeuvre. It became a prototype he would return to again and again over his long career. It would lead him straight to the image of a ruined temple hewn from a rocky outcrop in the sea that still among his most haunting and most famous, The Island of the Dead.

Cat. 2 Figures:

Cat. 2a Arnold Böcklin, Isle of the Dead, 1880, oil on canvas, 111 × 155 cm, Kunstmuseum Basel

Cat. 2b Arnold Böcklin, Villa by the Sea, 1865, oil and tempera on canvas, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Sammlung Schack, Munich

Cat. 2c Arnold Böcklin, Horse and Rider, detail from Cat. 2

Cat. 2d Carl Gustav Carus, The Erlking, 1825, oil on canvas, 71 x 54 cm, destroyed in the 1931 fire of the Glaspalast, Munich

[i] See Justine Hopkins’s article on the artist in The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Böcklin painted a total of six versions in quick succession: May 1880 (Kunstmuseum, Basel); June 1880 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); 1883 (Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin); 1884 (destroyed in Berlin during World War II); 1886 (Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig); see for images https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isle_of_the_Dead_(painting).

[ii] Goethe 1782.